Several questions have been raised about what WhatsApp can and cannot do, in an end-to-end encrypted messaging environment, after it filed a lawsuit against the Indian government over the IT Rules 2021 arguing that the rules are unconstitutional. People have raised questions about what issues WhatsApp might have in tagging messages with the identification information of a user when it collects metadata on users; suggested that it is only a minor modification to end-to-end encryption for it to add that tag; and questioned how WhatsApp tracks forwarded messages.

MediaNama compiled a list of such questions (many of which users sent us via Twitter), and we’ve got them answered by independent security researcher Anand Venkatanarayanan:

End-to-end encryption and traceability cannot go hand-in-hand

Q1. Why cannot WhatsApp enable traceability without breaking E2E?

Anand Venkatanarayanan: A message between two parties typically contains:

- Routing information or Envelope (Sender ID, Receiver ID).

- Content

Like a typical post office that just looks at the envelope to deliver mail, WhatsApp only looks at the receiver ID (in this case, a device associated with a phone number) and delivers the message when the receiver comes online. The content (inside the envelope as in our mail example) is encrypted via encryption keys that are known only to the sender and the receiver and these keys change for every message.

The encryption keys are exchanged between the sender and the receiver before sending the message without WhatsApp knowing about it through a cryptographic method called Diffie-Hellman key exchange. So all that WhatsApp knows is Sender, Receiver and content (which is gibberish because of encryption), and like a typical post office, it does not create a copy of the content after the message is delivered.

The IT Rules demand WhatsApp to not only keep a copy of the content for every message sent within India (on average several billion messages are exchanged every day within India) but also expects them to answer a question from law enforcement such as, who sent “Anand does not like Nikhil.”

Consider the implications of this request. To implement it, WhatsApp either needs to store the plain text of every message, which means breaking up E2E entirely or store the hash value of every message.

The hash value lookup is also problematic because Hash (Encrypted Message) will not be equal to Hash (Unencrypted Message) and WhatsApp only has access to encrypted messages. Further, the encryption keys change every message and are not known to WhatsApp at all. So when law enforcement serves a request to WhatsApp to find out the originator of the above message, what can it do, even if it stores every encrypted message ever sent?

The simple answer is NOTHING because every message is encrypted and encryption keys change for every message, and WhatsApp has no data to match the request.

Q2. Why cannot WhatsApp develop an alternate end-to-end encryption technology that meets traceability requirements?

Anand Venkatanarayanan: The simple answer is no one in the world who studies cryptography knows how to do it. The request is analogous to asking a gynaecologist, “Why can’t men become pregnant by transplanting a womb into their bodies”. It is a very easy question to ask with no reasonable answers. One way to think about the IT Rules is the government mandating a law, which assumes that such a technology already exists in a highly mathematical domain of cryptography and is just a matter of engineering it. Unfortunately, that assumption is wrong, and policymakers do not seem to understand that just like how passing a law cannot make men pregnant, a law cannot make mathematics behave in the way the government wants.

Q3. There is a term DPI (Deep packet inspection) in cybersecurity, which a firewall gateway uses to check if any malicious file is transferred via an encrypted tunnel. The firewall captures the encryption key before the communication even begins. Using the encrypt key, the firewall will read all the packets (data) to make a threat assessment. If a firewall gateway can make such eavesdropping, why cannot WhatsApp make it mandatory to send a copy of the key to the WhatsApp server for peer-to-peer communication to begin?

Anand Venkatanarayanan: This is not true. If it was, we need not do encryption at all and no public internet is safe. The TLS standard defines the encryption key exchange protocol and has stood the test of time.

DPI is something else. It allows a middlebox (a router) to look at packets flowing between a particular host and all other hosts it talks to and detect the application name (there are many applications such as SSH, HTTP, VoIP that are built on top of IP Layer) and combine it with network intelligence to generate application usage statistics.

Consider the example of OneDrive. The hostnames and ports to which traffic flows are generally known (See here). This allows a router to look at destination IP addresses, destination ports and conclude that the traffic is flowing to the OneDrive application. Similar analysis can be conducted for other services like Spotify, Gaana, NetFlix, Google Doc and so on.

What DPI allows is to get a full list of applications that a particular host or a broadband connection consumes and hence allows telecom companies and ISPs to draw a very good profile of a user/broadband connection. Monetizing this intelligence and offering variable speeds/application is what the net neutrality fight was all about.

It is possible to run DPI on even home routers with the appropriate tools installed and create “Application blocklists” or “Application degrade” (Reducing the bandwidth for a possible application thus throttling it) based on consumption patterns. For instance, my home network router in which I have installed DPI shows me things like below:

Corporate networks (within large organizations), however, are different because they can use web proxies to route traffic to the internet. Every device within the corporate network must typically be in the “Approved Device List” and are configured to trust certificates from the corporate’s Certificate Authority. This allows the web proxy to intercept even HTTPS connections (called SSL Bump or SSL Peek). In some jurisdictions, however, this approach is not considered ethical, as it involves a permanent snooping mechanism on the end-user device.

None of the above, however, applies to the public internet, where web proxies are installed and used to decrypt traffic. It would not anyway work unless the device itself is configured to use a proxy and is sold to the user without them knowing about it.

Q4. If messages are E2E, how come WhatsApp messages are leaked on news channels?

Anand Venkatanarayanan: First, law enforcement seizes the devices and forces the holder to unlock the devices or uses tools like Cellebrite to extract data. Then they leak it to news channels illegally.

Q5. Will Signal, Telegram, and Apple (iMessage) have to break End to End Encryption as well?

Anand Venkatanarayanan: Yes.

Q6. Assuming WhatsApp has implemented the Signal protocol properly, messages should also have PFS (perfect forward secrecy), right? Do you see any impact when adding traceability into the service?

Anand Venkatanarayanan: If the same encryption key is used for encrypting every message between a sender and a receiver, an adversary can first record all the messages and then somehow compromise the encryption key, which will allow them to decrypt all future messages as well. One way to defeat this threat is to always keep changing encryption keys. It could either be done on a per message basis or on a per session basis. Either approach works and gives Perfect Forward Security.

PFS is one reason why adding traceability for the first originator will break E2E as explained in answer to Q1.

Q7. How do you think the data will be decrypted or the entire model of encryption will be resigned, and how will it affect the users?

Anand Venkatanarayanan: The only way to implement the traceability rules is to fully break E2E. It will be similar to the SMS model of the 2000s era.

Q8. How does Signal protocol work?

Anand Venkatanarayanan: A non-technical explanation is available as a response to Q1. A detailed technical post is available here.

Q9. If WhatsApp were to agree and build in traceability, surely they wouldn’t weaken the service globally? Do you think we might have a “local” WhatsApp version that’s “compliant”?

Anand Venkatanarayanan: Yes. If the rules are not struck down, then we would be in a similar situation like China, where locally developed apps that do not have E2E will compete with each other for market share and global players like WhatsApp, Signal etc. have to either exit or would be blocked.

It is also very likely that WhatsApp may have to develop a “no-encryption” app that is specific only to India. Given the market reality, it might consider it as not a good investment and simply exit.

The “forwarded many times” label does not break E2E

The most popular argument that WhatsApp is not E2E is questioning how the “forwarded” label feature works. For instance, in a panel discussion in Mirror Now, Mr Brajesh Singh, IG Maharashtra, argues that “How does WhatsApp know about Forwarded Messages”. Jiten Jain and Shailesh Tiwary take this argument one level further and say that traceability is only an intent problem but is not a technical problem because they are already doing that for message forwarding. These arguments are not new and are, in fact, the basis of the Kamakoti proposal to add “First Originator” to the Madras HC, the incorrectness of which has been dealt with in detail before.

Q10. How does the “forwarding many times” tag work for WhatsApp without breaking end-to-end encryption?

Anand Venkatanarayanan: When a message is forwarded from a user’s device, two extra fields are added as part of the message itself (Forwarded: True, ForwardCounter: 1). As it keeps getting forwarded, the counter gets incremented, and once it reaches a threshold (say 100), the message is shown in everyone’s device as “highly forwarded” or equivalent.

A mental model that may help visualise this process is to imagine someone sticking a small note inside the envelope of a regular letter, which indicates if the message is forwarded and how many times. Every time someone opens the letter, reads and forwards the message, the hidden field is incremented, content is copied, encrypted and sent to a different set of recipients.

Hidden fields within the message payload guarantee that WhatsApp does not know anything about message forwarding but users still know about forwarded messages and it’s velocity. This scheme however suffers from the “rogue client” problem, where custom made apps that run a different code can remove these hidden fields.

I have come across several of these custom apps used by political parties in the 2018 and 2019 elections.

Q11. Why can’t official WA clients digitally sign their messages to prevent third-party clients from altering content?

Anand Venkatanarayanan: Instant messages are not emails. The Signal protocol that WhatsApp uses has inbuilt cryptographic deniability where encryption keys change for every message. This constant change of encryption keys offers forward secrecy (if an attacker can compromise one encryption key, they can only read that one message but not all messages sent before and after). Digital signatures are an anti-thesis of E2E as they break forward secrecy.

Q12. How did WhatsApp block link forwarding in the NZ mosque attack without seeing the contents of the message?

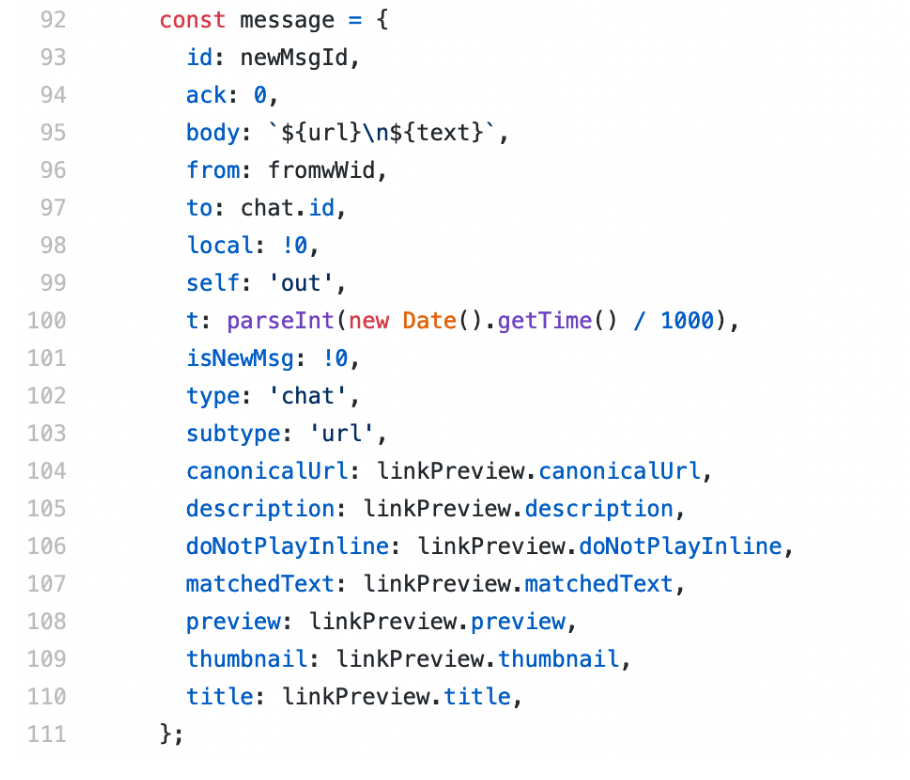

Anand Venkatanarayanan: Link previews are done on the client-side. When a link is pasted on a chatbox, the client just fetches the image and the heading/sub-heading and makes it a message (See this code fragment below. Here the body is the URL, but two extra fields “preview” and “thumbnail” are added).

The NZ mosque attack forwarding was disabled by taking down the URLs that hosted the video and not by looking at the message. When the URL is taken down, then the link preview automatically fails. While the plain URL can still be forwarded, it would not work because it has been taken down by the domain webmaster that hosted it (or law enforcement brought the domain itself down by talking to the domain registrar).

While forwarded messages will still retain the thumbnail, title and the URL, the actual content when clicked, will not work.

Using metadata to trace the originator

Q13. Why cannot originator data be part of the metadata that WhatsApp collects?

Anand Venkatanarayanan: The question answers itself if we consider that the data that WhatsApp sees as an intermediary is the triplet (Sender, Receiver, Content). The content is fully garbled and protected by ever-changing encryption keys, which even WhatsApp is unaware of. While it does collect activity records such as (Sender, Receiver, Time) and other meta-data about groups, there is no way to collect originator information and tie it with a garbled message, with ever-changing encryption keys as explained before.

Q14. Can one identify the sender/originator using metadata?

Anand Venkatanarayanan: The simple answer is no, and if it were possible, WhatsApp would not have sued the government.

Q15. Is metadata also encrypted?

Anand Venkatanarayanan: No. WhatsApp does collect meta-data for various reasons, including for complying with law enforcement requests.

Contexts where E2E is not applicable

Q16. How does WhatsApp deal with content that users report as spam if the messages are encrypted?

Anand Venkatanarayanan: When users report spam, they report it from their device, which already has decrypted content. The report sends a certain number of already decrypted messages in your device between you and the other person/group for WhatsApp to analyse the nature of messages and take further action.

Q17. How do WhatsApp backups (Google Drive, iCloud) work, given that they are not encrypted?

Anand Venkatanarayanan: Apps in mobile devices use plain files or light databases (SQLite) to store data. WhatsApp is no different. Hence a backup simply creates a zip version of these files and databases and uploads it to iCloud or G-Drive and can be recovered later by a restore operation.

Q18. Without breaking end-to-end encryption, how can WhatsApp help a government agency in tracking criminal activities?

Anand Venkatanarayanan: They do share quite a lot of meta-data on request. Law enforcement is typically expected to do some work before asking for meta-data. They should at least know the phone number(s) that are suspicious based on the investigation done before approaching WhatsApp. However, worldwide their preference is always to get this done quickly by leaning on the intermediaries to build mass surveillance systems (X-Key score is one such example as revealed by Snowden).

Encryption in WhatsApp Business

Q19. Can you elaborate on end-to-end encryption vis a vis private and business chats?

Anand Venkatanarayanan: In private chats, the number of participants is either 2 (1 to 1) or more than 2 (Group). In business chats, the number of participants is either 2 (Business and you) or more than 2 (Business, you and Business delegates). A business delegate can be an organisation that manages the business account for the business (Like Twilio, Ozonetel or even Facebook) or other business representatives (like customer support organisations).

Irrespective of whether it is a business chat or a private chat between individuals, the messaging between the parties still uses the same E2E design.

Unlike individual users, however, business chats can be stored forever for various compliance purposes (Refunds, Tax laws etc.) and could be linked with your purchases, payment transactions, your physical location etc. (Imagine ordering food from your local restaurant via WhatsApp business API, paying via UPI and getting it delivered to your home).

Hence the right way to think about business chat is that even though the technological backbone is E2E, since various parties may have access to the content, once it is delivered to their devices (or to other systems via Business API), the privacy guarantees of E2E might not apply strictly.

Q20. Are business chats accessible to WhatsApp and the Indian government?

Anand Venkatanarayanan: It is reasonable to assume that they would be. For instance, business chats in WhatsApp use template messages (like TRAI-mandated message templates for SMS as part of its DLT regulations), and these templates must be pre-approved. Further, if the business uses third party delegates, they would have access to your chats, and digital payment transactions would fall under the local laws, including PMLA (Prevention of Money Laundering Act) and businesses including WhatsApp may be asked to turn this over to law enforcement if an investigation warrants it. Hence these chats will be stored for longer periods (typically 5 to 7 years).

The legitimacy of WhatsApp’s intentions

Q21. How can you trust a closed source like WhatsApp (owned by Facebook) on what they promise? Is there a way to check their encryption claims?

Anand Venkatanarayanan: These days no apps are truly closed because reverse-engineering them to create a working copy is no big deal (the venom JS client is one such example). This allows us to verify claims made about E2E to a large extent. The server-side code not being available for inspection is, of course, a concern. Still, by inspecting the Signal app client and server code and WhatsApp client and carefully comparing the differences, one can be reasonably sure if WhatsApp is truly E2E (they are to a large extent).

Q22. Are there any viable open-source clients for WhatsApp? Viable as in full functionality and with some degree of credibility as to security?

Anand Venkatanarayanan: Unofficial clients exist in the wild but are mostly traded for other reasons. However, JS OSS clients exist, such as Venom.

Q23. How does WhatsApp’s lawsuit stand when compared to its new policy of sharing some data with Facebook?

Anand Venkatanarayanan: The lawsuit against the government and the data sharing policy are two different things but are also related because they create massive privacy issues for users.

The WhatsApp data sharing policy with Facebook is a ham-handed way to obtain user consent for allowing businesses to reach them via WhatsApp Business accounts and has been rightly flagged as problematic by the EU countries. Concerns about linking purchases with ads, payment transactions and PII to get a 360 profile of activities across these two products are legit. These concerns have now forced WhatsApp to suspend its privacy policy change until the work in progress personal data protection bill is passed as law. It remains to be seen how this situation would evolve.

However, the IT rules go even further than that. They mandate a full breakup of E2E indirectly and give access to any message to the government by asking WhatsApp to build a mass surveillance program like X-KeyScore. So we have a unique situation, where the government mandates a much worse privacy violation by asking WhatsApp to implement traceability by using its own problematic data sharing policy with Facebook as a precedent by pushing the deeply problematic view that “They already violate everyone’s privacy and know everything. So why can’t they violate it completely and do what we are asking them to.”

As the EU countries have shown, a fair response would have been to order the freezing of the rollout of data sharing policy with Facebook while figuring out collaborative solutions to untie the E2E knot, but instead the government chose a cynical response that can compromise all our privacy, even more.

Q24. How does WhatsApp earn when it cannot read our messages? It’s a free service and not an ad-based revenue model as well?

Anand Venkatanarayanan: WhatsApp Business is supposed to be that model.

Intentions of the government

Q25. When Pegasus is there, then why do we need this law?

Anand Venkatanarayanan: Pegasus is a cyber weapon. It is a custom crafted malware with specific service guarantees by the NSO. While typical malware operators sell only code, Pegasus not only sells code but also sells infrastructure that allows the code to be deployed and view compromised devices with a dashboard UI that allows the buyers to get more data from the compromised devices and even plant documents.

It is typically used by intelligence agencies around the world to selectively target individual or individual(s) and is deployed by sending them a malware link or a secret SMS message that will download and install the malware on their devices.

While Pegasus in general works and is great for targeted surveillance, it is also expensive. The operational cost for hacking devices in 2016 was around $700,000 for ten devices, with an additional $500,000 for installation services (Dashboard, Operating Console etc). Hence if the government wants to monitor 1000 devices using Pegasus, the cost quickly escalates to $70 million and above, and at a million devices, it might need several billion dollars.

Hence it is far easier to pressurise intermediaries to build surveillance back doors via IT Rules and make it a condition for doing business. This model is tried and tested and is done while telecom companies are granted licenses to operate mobile networks and internet services in India, and even standards exist for such monitoring.

E2E, however, renders all these standards pointless as it can’t be broken except at the end-user level (hence the use of Pegasus). Hence one way to think of these rules is bringing back free-for-all surveillance for law enforcement as a technical standard indirectly through a legal mandate (which is, of course, not possible).

Q26. According to FAQ, WhatsApp maintains transaction logs of messages delivered or not for 30 days. It allows US law agencies access to those. Transaction logs would include message sender and receiver. Why can’t it be provided to law agencies in India?

Anand Venkatanarayanan: Metadata sharing is always done based on request. But it can only be done when law enforcement agencies (LEA) provide them with a list of user IDs, requiring LEA to do some initial investigation first.

However, not every LEA is equal. In India, investigative capabilities are not on par with elsewhere, which creates pressure for shortcuts and the IT rules 2021 is an outcome of such pressure.

Q27. What is your take on privacy Vs State? A person should have the right to privacy; how can we honour this privacy along with the integrity of state and country?

Anand Venkatanarayanan: Governments all around the world have engaged in mass surveillance, as the Snowden affair revealed. They acted in a manner that is against their own laws. This forced users to demand better privacy and E2E is a natural evolution of that demand. One way to think about the stand-off is that, finally, citizens have a technical tool that has moved the needle forward on unlawful interception and surveillance. We have had several instances of this problem even in India (The Radia Affair, for example).

With E2E, law enforcement is now forced to work harder to show probable cause for information requests from intermediaries, which they are unhappy about. Hence the demand for traceability and other measures which are disguised as reasonable requests but which are not possible without breaking encryption.

Also Read

- How WhatsApp Deals With Child Sexual Abuse Material Without Breaking End To End Encryption

- Summary: WhatsApp Alleges IT Rules Are Unconstitutional In Lawsuit Against Indian Government

- IT Rules 2021: CEO Will Cathcart Says WhatsApp Hopes To Find Solution To Traceability Without Breaking Encryption

- Identifying A Message’s Originator Undermines End-To-End Encryption: Internet Society

- Transcript And Video: MEITY’s Rakesh Maheshwari On IT Rules, 2021; Traceability, Intent, Compliance Timelines

- Supreme Court Directs Madras HC To Transfer All Files In The WhatsApp Traceability Case