By Varsha Rao

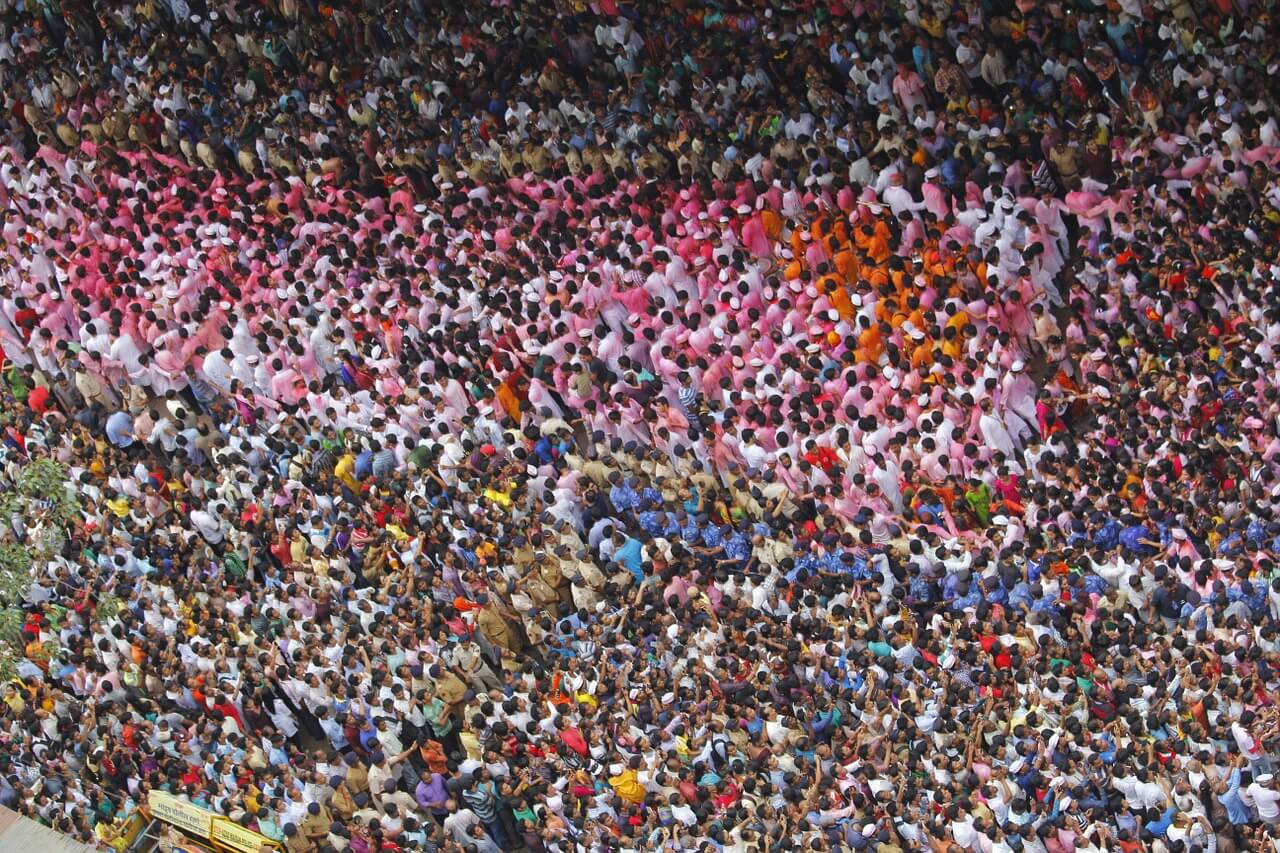

With the publication of Special Counsel Robert Mueller’s much-awaited report on Russian interference in the United States Presidential Elections of 2016, the threat of hacking and misinformation campaigns to influence elections is taking centre-stage yet again. Closer to home, the discussion has become more pertinent than ever before. In a democratic process of gigantic proportions, 900 million Indians across 543 constituencies are expected to cast their vote in 7 phases to elect a Government for the next five years.

The gravity and significance of the ongoing General Elections to the Lok Sabha thus begs the question – how susceptible is the world’s largest democracy to cyber interference?

Interfering in an election in the digital age involves a two-pronged attack – firstly, by influencing the political inclination of the electorate via misinformation campaigns on social media platforms, and secondly, by manipulating the electoral infrastructure itself. This article will focus on the latter, more specifically, the infrastructure and processes administered by the Election Commission of India.

Voter Registration Databases and Election Management Systems (EMS)

Unfettered access to voter registration databases arms malicious actors with the ability to alter or delete the information of registered voters, thereby impacting who casts a vote on polling day. Voter information can be deleted from the electoral rolls to accomplish en-masse voter suppression and disenfranchisement along communal and religious lines in an already polarized voting environment. The connectivity of voter databases to various networks for real-time inputs and updates make them highly susceptible to cyberattacks.

The manipulation of election management systems (EMS) can have an even wider impact on the electoral process. Gaining access to the Election Commission’s network would be akin to creating a peephole into highly confidential data ranging from deployment of security forces to the tracking of voting machines.

Election Commission staff can be targeted via phishing attacks in a manner similar to the cyberattacks executed during the 2016 U.S. Elections. Classified documents of the U.S. National Security Agency (NSA) as well as Special Counsel Robert Mueller’s report confirm that hackers affiliated with the Russian government targeted an American software vendor enlisted with maintaining and verifying voter rolls. Thereafter, posing as the vendor, the hackers successfully tricked government officials into downloading malicious software that creates a backdoor into the infected computer.

The Election Commission has made proactive attempts to improve the cyber hygiene of its officials by conducting national and regional cybersecurity workshops and issuing instructions regarding vigilance against phishing attacks and securing and shredding of contents on storage media. Furthermore, Cyber Security Regulations have been issued to regulate the officers’ online behaviour. A Chief Information Security Officer (CISO) was appointed in December 2017 at the central level and Cybersecurity Nodal Officers have been appointed in at the State-level.

The Election Commission has also addressed spoofing attempts by taking down imposter apps from mobile phone app distribution platforms. According to newspaper reports, the Election Commission has carried out a third-party security audit of all poll-related applications and websites and enabled Secure Sockets Layer (SSL) on the Election Commission website to encrypt information exchanged between a user’s browser and the website.

There is no doubt that cybersecurity risks are constantly evolving, and it remains imperative for the Election Commission to conduct systematic and periodic vulnerability analyses in collaboration with security auditors to update Election Commission systems and software.

Electronic Voting Machines

An EVM is made up of two units – a Control Unit and a Balloting Unit, linked by a five-metre long cable. The Presiding/Polling Officer uses the Control Unit to release a ballot. This allows the voter inside the voting compartment to cast their vote on the Balloting Unit by pressing the button labelled with the candidate name and party symbol of their choice. An individual cannot vote multiple times as the machine is locked once a vote is recorded, and can be enabled again only when the Presiding Officer releases the ballot by pressing the relevant button on the Control Unit.

While the Election Commission has reiterated time and again that EVMs are tamper-proof, the machines have come under criticism from security researchers and computer scientists. To defend the integrity of EVMs, the Election Commission frequently cites the simplistic design of the machine. The EVMs are battery-operated in order to be functional in parts of the country that do not have electricity access. Additionally, they are not connected to any online networks nor do they contain wireless technology, thereby mitigating the possibility of remote software-based attacks. While these factors certainly reduce the potential for EVM hacking, they do not justify the Election Commission’s unshakeable belief that EVMs are infallible.

The most explosive demonstration of EVMs being susceptible to hacking attempts was carried out all the way back in 2010 by a Hyderabad-based technologist, Hari K. Prasad in collaboration with J. Alex Halderman, an American computer science professor and Rop Gonggrijp, a hacker who campaigned to decertify EVMs in the Netherlands.

Various personnel interact with the EVM, right from the beginning of the supply chain to the officials and staff responsible for its storage and security before and after polling. In a paper published by Hari Prasad and his team, two methods of physical tampering were tested and demonstrated. The first method is to replace the Control Unit’s display board which is used during the counting process to show the number of votes received by candidates. The dishonest display board, on receiving instructions via Bluetooth, would have the ability to intercept the vote totals and display fraudulent totals by adjusting the percentage of votes received by each candidate. The second method involves attaching a temporary clip-on device to the memory chip inside the EVM to execute a vote-stealing program in favour of a selected candidate.

The physical security of the EVM takes on manifold importance in light of the above. The Election Commission has strict procedures in place to transport and store the machines, employing GPS and surveillance technology. Storage spaces known as ‘strong rooms’ having a single-entry point, double lock system and CCTV coverage are utilised. However, there have been frequent news reports about cases of EVM theft, strong room blackouts as well as unauthorized access.

The Election Commission has argued that since mock polls are conducted before official polling commences, any malfunctions or tampering attempts will be detected before it can impact the electoral process. However, this countermeasure does not address the possibility of attackers programming their tampering devices to kick into gear only after the EVM has recorded a set number of votes, thereby skipping over any mock poll entries.

Furthermore, while the source-coding or the writing of the software onto the EVM chip is done by Indian public sector undertakings (PSUs), the microchips themselves are imported from the United States and Japan. Since the EVM chip is a one-time programmable chip, it can neither be read, copied or overwritten. The benefit of this feature is that they cannot be re-programmed by malicious actors. However, the masking also has a downside – in the event that any vulnerabilities are inserted into the chip or source code during the movement of the machine components along the supply chain, it may not be possible to detect the vulnerability.

Introducing a Voter Verifiable Paper Audit Trail (VVPAT) system was widely touted as second layer of verification to catch any EVM malfunctions. It was only at the insistence of the Supreme Court that the Election Commission agreed to roll out EVMs with VVPATs for the ongoing General Elections.

When a vote is cast, the battery-operated VVPAT system prints a slip containing the serial number, name and symbol of the candidate, which is available for viewing through a transparent window for a few seconds. Following that, the slip falls into a sealed drop box.

An effective VVPAT audit is an important solution to the vulnerabilities plaguing EVMs. The Election Commission’s procedure for VVPAT audit involved counting of VVPAT slips in one polling booth per Assembly segment for the General Elections. The Supreme Court had to intervene again – at the insistence of Opposition parties – for the Election Commission to increase the audit from one EVM to five per Assembly segment. The Court did not accept the Opposition parties’ plea to have 33-50% votes verified.

The call for extensive VVPAT slip audits has been an ongoing battle, with bureaucrats, politicians and experts on the frontlines. Former bureaucrats had written to the Election Commission to increase the audit sample size to 50 machines per 1 lakh booths instead of 5-6 machines. A former Chief Election Commissioner has proposed that the two runners-up in a constituency may be the given the option to randomly select two EVMs each for a VVPAT slip audit – a procedure similar to the Umpire Decision Review System in cricket. Another proposed method known as the Risk Limiting Audit requires the ballots to be audited until a pre-determined statistical threshold of confidence is met.

The resistance displayed by the Election Commission to introducing VVPAT slip audits as well as expanding the sample size of the audits is alarming. The Chief Justice of India even reprimanded the Election Commission for “insulat[ing] itself from suggestion for improvement”. Unsurprisingly, the Court had to reassure the Election Commission that in making recommendations to improve the electoral process, it was not casting aspersions on the functioning of the body.

While it is commendable that the Election Commission has embraced the implementation of technology like EVMs in the electoral process, it is becoming clear that it has not incorporated the tradition of vulnerability research and software patching to prevent further exploits. Security researchers must be provided time and unfettered access to test the efficacy and security offered by EVMs. Hacking challenges should not be restricted to EVM replicas or superficial tinkering on the external body of the EVM.

It is understandable for an authority like the Election Commission to focus on protecting the integrity of the institution as well as the election infrastructure. However, pointing out flaws in the EVM technology is not equivalent to an attack on the institution of the Election Commission. While the entire process of elections is built around trust – be it trust in the method of casting votes or trust in the authority tabulating the votes – it is the responsibility of those in whom the trust of the electorate is reposed to ensure transparency at every stage and welcome public scrutiny, especially when new and complex technology is being employed.

Varsha is a researcher with the Centre for Communication Governance at National Law University Delhi.

*

This article was first published on CCG-NLUD’s blog, its been cross-posted with prior permission.